Last Updated on February 4, 2026 by DarkNet

Email forwarding can simplify inboxes, but it affects security and deliverability. Learn how it works, where it helps, where it hurts, and how to set it up safely.

What Email Forwarding Is (and How It Differs From Aliases)

Plain-language definition and flow

Email forwarding is an automated process that sends a copy of messages arriving at one address to another address. It is usually configured on the receiving server, not in the sending app. The original message headers are preserved, though some systems add a small wrapper or tag. Message format follows standards such as RFC 5322.

Typical flow:

Sender <sender@example.com> | v Original domain MX receives message | v Forwarding rule triggers | v Forwarder re-addresses and relays the same message | v Destination inbox receives forwarded copy

Depending on the provider, the envelope sender may be rewritten, and authentication checks can pass or fail. These details affect whether the forwarded message lands in the inbox or spam.

Forwarding vs alias: what changes and what stays the same

An alias is an extra address that delivers into the same mailbox without relaying elsewhere. Forwarding relays mail to a different mailbox. With an alias, you still read mail in the original account. With forwarding, you read in the destination account. Aliases avoid deliverability side effects because there is no second hop. Forwarding introduces a second hop that can affect SPF, DKIM, and DMARC alignment.

Where forwarding happens: server-side vs client rules

Server-side forwarding runs on the mail server before you open your inbox. Client rules run in your mail app, which means the app must be running to forward. For reliability and compliance logging, server-side forwarding is generally preferred. Client rules are better for personal triage where delivery timing is less critical.

Common Email Forwarding Setups: Personal, Business, and Team Use

Personal use cases: consolidating inboxes during transitions

People often forward from an old ISP or school address to a long-term address, or from multiple hobby domains into a single inbox. This simplifies life while contacts update their address books. Keep the old mailbox accessible for a while because replies may still route there.

Business use cases: role addresses and vendor routing

Companies forward role addresses like info@ or billing@ to the right person or team. They may temporarily forward from a retiring brand domain to a new domain during a migration or merger. Forwarding can also route vendor alerts into a ticketing inbox. Each case requires attention to retention requirements and spam filtering effects.

Team scenarios: triage, escalations, and on-call rotations

Teams use forwarding to escalate incidents to on-call devices, to mirror messages to an archive, or to copy critical alerts to a standby inbox. Use guarded rules so you do not generate duplicates or loops, and document who owns the forwarding logic.

Pros of Forwarding Email: Convenience, Organization, and Continuity

Single inbox convenience

Forwarding lets you centralize reading and response in one place. It reduces context switching and can speed up response time. For individuals, this replaces juggling multiple apps. For teams, it reduces missed messages when people are out.

Continuity during moves or mergers

During domain changes or email platform migrations, forwarding helps maintain continuity while DNS and contacts catch up. It buys time to communicate the new address and avoid lost inquiries.

Lightweight routing without new tools

Basic forwarding rules are simple to set up and maintain. There is no new user interface to learn, and costs are minimal compared to deploying ticketing or shared inbox platforms for small volumes.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Centralizes multiple addresses into one inbox | Can break SPF and DMARC alignment, causing spam or bounces |

| Supports temporary transitions and rebrands | Risks unauthorized auto-forwarding by attackers |

| Low setup overhead compared to new tools | May violate privacy, retention, or data residency rules |

| Works across providers and domains | Duplicates and loops possible without guardrails |

| Simple to explain to non-technical users | Harder to audit and monitor than single-mailbox access |

Cons of Forwarding Email: Security, Privacy, and Compliance Risks

Security pitfalls: account takeovers and unauthorized rules

Attackers who compromise a mailbox often create silent forwarding rules to exfiltrate mail. These rules can persist even after a password reset. Enforce multi-factor authentication, block external auto-forwarding unless approved, alert on new rules, and regularly audit mail flow logs.

Privacy and data residency concerns

Forwarding may move personal or regulated data to systems that do not meet your policy requirements. This can breach contracts or regulations. Keep sensitive mail in controlled systems and use delegated access instead of forwarding whenever data scope matters.

Compliance and retention gaps

When you forward out of a controlled archive, you can lose e-discovery coverage, legal hold, or retention tags. If forwarding is necessary, ensure the destination system has equivalent retention and export capabilities, and that journaling or archiving captures the forwarded path.

Deliverability and Spam Impacts When Messages Are Forwarded

Why forwarding breaks sender reputation signals

Forwarding creates a new SMTP hop. If the forwarder relays the message using its own IP without rewriting the envelope sender, SPF checks at the destination will often fail because the receiving server sees the forwarder’s IP sending mail for the original domain. DKIM usually carries through if the body and headers are unchanged, but even small modifications can invalidate the signature.

Spam filtering side effects and false positives

Spam filters use IP reputation, authentication, and content scoring. Forwarding mixes signals from the origin with the forwarder’s IP. If the forwarder also relays spam from other sources, your forwarded legitimate mail may be penalized. Mailing list tags or added footers can alter content scores. Bounces may be sent back to the original sender, creating backscatter risk.

How to mitigate: SRS, ARC, and smart routing

Some forwarders implement Sender Rewriting Scheme to rewrite the envelope sender so SPF checks can pass at the next hop. Authenticated Received Chain can preserve authentication results across hops. When possible, use redirect or alias features that avoid body modifications, and prefer providers that support SRS and ARC. Keep forwarding trees shallow and avoid chaining through multiple services.

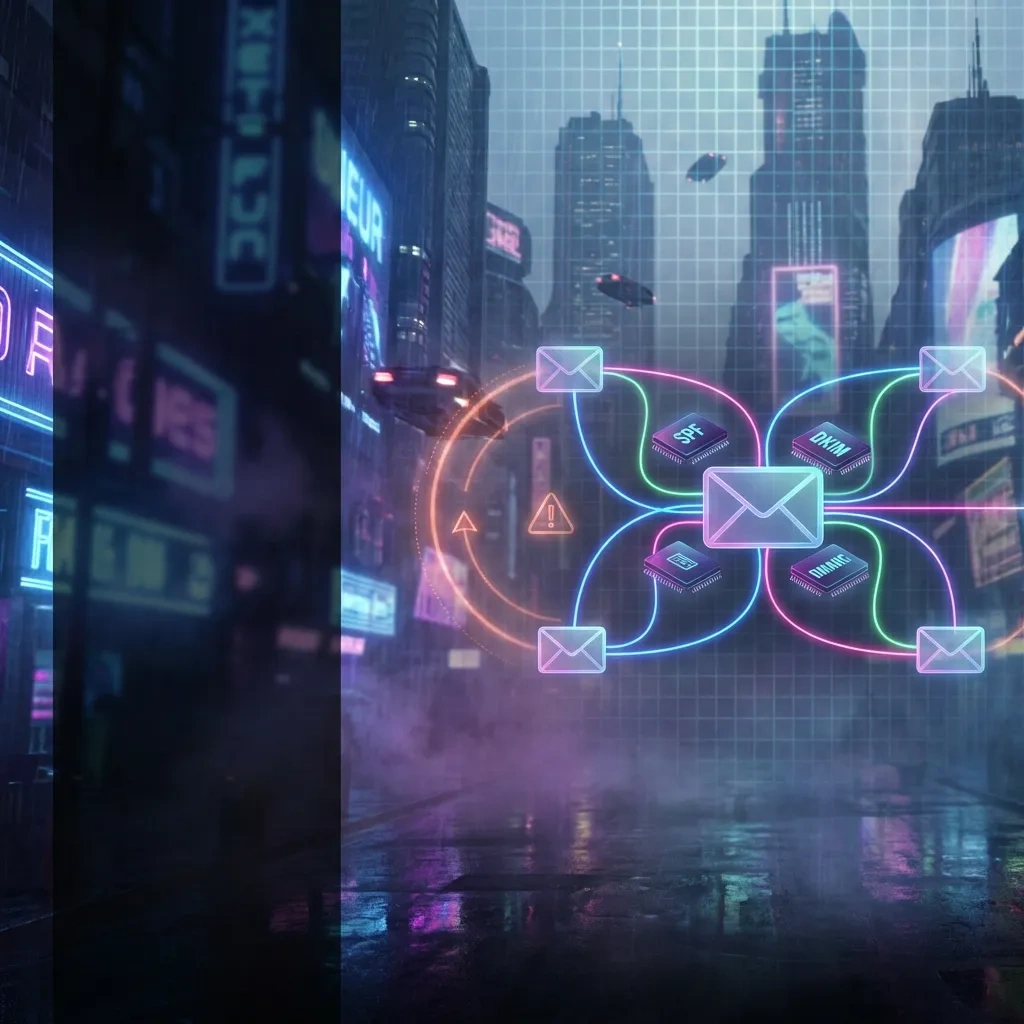

Authentication Basics: SPF, DKIM, and DMARC in Forwarding Scenarios

SPF alignment and why it often fails after forwarding

Sender Policy Framework checks whether the sending IP is authorized to send for the domain in the visible From or envelope sender. In simple forwarding, the forwarder’s IP is not authorized by the original domain, so SPF fails at the destination. Sender Rewriting Scheme can help by changing the envelope sender to a domain the forwarder controls, restoring SPF alignment for that hop. See RFC 7208.

DKIM survives intact if not modified

DomainKeys Identified Mail signs headers and parts of the body. If the forwarder does not modify signed fields, DKIM can still validate at the destination. Minor changes like subject tags or footer injections can break signatures. See RFC 6376.

DMARC policy outcomes on forwarded mail

DMARC relies on aligned SPF or DKIM. If DKIM remains valid and aligned, forwarding usually passes DMARC. If DKIM fails and SPF is not aligned, DMARC may fail, and receivers may quarantine or reject per the sender’s policy. DMARC reporting helps diagnose these failures. See RFC 7489.

Glossary: SPF, DKIM, DMARC, SRS

- SPF: A DNS policy that lists IPs allowed to send for a domain. Evaluated on the SMTP envelope sender.

- DKIM: A cryptographic signature added to messages by the sending domain so receivers can verify integrity.

- DMARC: A policy that tells receivers how to handle messages when SPF and DKIM fail or do not align, and provides reporting.

- SRS: Sender Rewriting Scheme, a method forwarders use to rewrite the envelope sender to keep SPF results meaningful.

Related standard for preserving authentication results across hops: Authenticated Received Chain. See RFC 8617.

Forwarding vs Alternatives: Aliases, Shared Inboxes, and Rules

Aliases: same mailbox, different address

Aliases deliver into the same mailbox under multiple addresses. They avoid second-hop deliverability loss, preserve retention and search, and are easy to manage. They are ideal when you control the receiving system and only need multiple addresses for one person or team.

Shared inboxes and delegated access for teams

Shared inboxes and delegated access let multiple people read and reply without copying messages outside the domain. They support assignments, internal comments, and consistent retention. For privacy and compliance, shared access is usually better than forwarding.

Client and server rules: copy, redirect, and archive instead

Rules can label, auto-assign, or move mail without relaying externally. Server redirect features can preserve the original From while delivering to another internal mailbox. For external recipients, prefer delegated access over external forwarding whenever feasible.

Best Practices for Safer Email Forwarding

Checklist: configure forwarding with security and delivery in mind

- Decide if forwarding is necessary. Prefer aliases, shared inboxes, or delegated access for internal scenarios.

- Use server-side forwarding. Avoid client-only rules for critical mail.

- Enable multi-factor authentication on both source and destination accounts.

- Limit who can create external forwarding rules. Require approvals and log changes.

- Choose providers that support SRS and ARC for better deliverability.

- Avoid modifying subjects or bodies on forwarded mail. Do not add footers that can break DKIM.

- Keep the chain short. Do not forward to another forwarder.

- Enable DMARC reports on your domain to monitor forwarded traffic outcomes.

- Set guardrails against loops. Block re-forwarding from destination back to source.

- Preserve copies where required. Ensure journal or archive systems capture forwarded messages.

- Do not forward sensitive data to personal inboxes. Follow data residency policies.

- Review spam folder and logs during rollout to catch issues early.

Access and privacy safeguards

Least privilege applies. Only forward what is needed to fulfill a task or transition. Mask or redact sensitive content upstream when possible. Document who receives forwarded mail and why. Periodically re-approve forwarding rules, and remove them when no longer needed.

FAQ: common questions answered

Does email forwarding keep my original email address private?

Not reliably. The original From address is visible to recipients and may appear in headers. Replies go to the visible From unless reply-to is set. Forwarding is not an anonymity tool.

Why do forwarded emails sometimes go to spam?

Forwarding can break SPF alignment and alter content, while mixing the forwarder’s IP reputation into the decision. If DKIM fails and SPF is not aligned, DMARC may fail, leading to spam or rejection.

What is the difference between an email alias and email forwarding?

An alias delivers to the same mailbox under another address. Forwarding relays to a different mailbox. Aliases avoid second-hop deliverability issues and keep data in one account.

How do SPF, DKIM, and DMARC affect forwarded messages?

SPF often fails after forwarding unless the forwarder uses SRS. DKIM can pass if headers and body are unchanged. DMARC passes if either SPF or DKIM aligns. See SPF, DKIM, and DMARC.

Is it safe to forward work email to a personal inbox?

Generally no. It can violate policy, weaken security controls, and expose confidential data. Use delegated access or managed mobile apps instead.

Can forwarding create mail loops or duplicate messages?

Yes. If destination rules point back to the source, or if multiple rules overlap, loops and duplicates occur. Prevent this with loop detection, unique tags, and strict routing rules.

What are best practices for forwarding role-based addresses like info@?

Prefer shared inboxes or help desk tools. If forwarding, limit recipients, enable SRS, avoid content modification, and archive messages for accountability.

Decision Checklist: When Forwarding Is a Good (or Bad) Fit

When forwarding is appropriate

- Short-term domain transitions where contacts still use the old address.

- Light personal consolidation across a few addresses with low sensitivity.

- Simple role routing in small teams when shared inboxes are overkill.

- Alert mirroring to a monitored mailbox with clear ownership and audit.

When forwarding is risky or the wrong tool

- Mail that includes personal, financial, health, or regulated data.

- Organizations with strict retention, legal hold, or residency needs.

- High-volume queues needing triage, assignment, and reporting.

- Any case where external forwarding would bypass DLP, archiving, or SSO.

Quick evaluation worksheet

- Purpose: what problem does forwarding solve, and for how long?

- Data: what sensitivity level will be forwarded, and to which jurisdictions?

- Controls: will MFA, archiving, SRS, and DMARC reporting be in place?

- Alternatives: would an alias, shared inbox, or delegated access meet the need?

- Ownership: who maintains the rule, and how is it reviewed and retired?

- Testing: has deliverability been tested with real messages and logs?

Key takeaways

- Email forwarding is simple but changes how authentication and spam filters behave.

- Pros include convenience and continuity. Cons include deliverability loss and security risk.

- SPF often fails after forwarding. DKIM can survive. DMARC depends on alignment.

- Support SRS and ARC when possible, and avoid modifying forwarded content.

- Prefer aliases, shared inboxes, or delegated access for internal or sensitive work.

- Use MFA, monitor for unauthorized forwarding, and follow retention policies.

- Keep forwarding temporary and documented, with clear ownership and review.

- Test deliverability and logs before relying on forwarding for critical communications.